Palazzo Poggi: Bologna’s Renaissance cabinet of wonder

Blink and you might miss the plain door at 33 Via Zamboni.

Push it open, and Bologna’s graffiti vanishes, replaced by echoing frescoes.

A hushed courtyard—muscular pilasters, a lone plaster Hercules—whispers of secret labs upstairs.

Ready to find out where Renaissance art flirts with cutting-edge science?

Palazzo Poggi: Renaissance home, idea factory

Cardinal Giovanni Poggi fused several medieval houses into a domus magna in the 1550s. Design credit bounces between Pellegrino Tibaldi, Bartolomeo Triachini and Galeazzo Alessi, but the result is calm authority in terracotta.

In 1711, velvet salons became labs for the newborn Istituto delle Scienze; by 1805 Napoleonic edicts had turned the palace into the University seat.

Closed, dispersed, re-united—since 2000, it has welcomed visitors again.

Frescoes to decode

Tibaldi’s ground-floor Odyssey casts Ulysses as a church diplomat.

Upstairs, Nicolò dell’Abate paints banquets, moonlit concerts, and a ceiling-wide Labours of Hercules, while Prospero Fontana adds Stories of David and riotous grotesques.

Evolving architecture

Note Morandi’s doubled pilasters, then the 1726 Specola tower and Carlo Francesco Dotti’s baroque reading hall—additions so seamless the building feels grown, not built.

Collections that changed science

Aldrovandi’s natural-history revolution

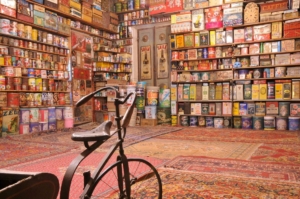

Ulisse Aldrovandi, the sixteenth-century professor who rebooted zoology, believed truth starts with the eye.

He roamed the Apennines sketchbook in hand, swapped shells and seeds with traders, and built a collection of 18,000 specimens—so many that jars invaded his bedroom.

Visitors called it the world’s first natural-history museum.

Standing before his wood-block matrices, you can almost smell the ink of the folios that helped Europe imagine nature for the first time.

His network of collectors

Princes mailed him crocodiles; pharmacists shipped exotic roots from Goa; sailors smuggled hummingbirds in rum casks.

Aldrovandi’s web spanned every continent then known and proved that collaboration, not solitude, fuels discovery.

Legacy and modern restart

Napoleonic reforms scattered the jars across new faculty museums, yet the 2000 reopening reunited highlights in their original rooms.

The result feels like stepping into a time capsule humming with twenty-first-century climate control.

Galli’s school of obstetrics

In 1758, Giovanni Antonio Galli installed Europe’s first obstetrics classroom here.

His recipe: teach theory at morning lectures, then make students practise manoeuvres on lifelike models by afternoon.

Wax panels showed pelvic anatomy, clay wombs demonstrated fetal positions, and a strange birthing chair tested everyone’s nerves.

Certification came only after you could guide a baby doll safely through the “birthing machine.”

Birthing machines and the “Venerina”

Center stage stands the Bolognese Venerina—a wax Venus whose torso opens like a cabinet to reveal lungs, liver, and a tiny foetus curled inside.

Equal parts science and sensuality, she embodied the Enlightenment conviction that beauty and knowledge share the same skin.

Impact on medical teaching

Galli’s hands-on method spread across Europe, shaping midwifery for a century.

Modern medical simulators trace their lineage to these eerily quiet wax rooms.

Plan your visit

A standard ticket costs €7, less than two cappuccinos, and students pay even less.

Doors usually open 10 a.m.–4 p.m. Tuesday to Friday and 10:30 a.m.–5:30 p.m. on weekends—always double-check the website before you set off.

Two easy hours let you greet Hercules, sketch a narwhal tusk, and decide with a friend whether the Venerina is beautiful or unnerving.

Ticket basics & La Specola

Inside, you’ll spot arrows to La Specola, the 1726 observatory perched over the rooftops.

It runs on different hours and its own ticket, so ask at the desk whether your legs—and timetable—can handle the extra climb.

Want the secrets, not the crowds?

I can arrange a private, art-history-focused tour of the University of Bologna—Palazzo Poggi included—led by a licensed local guide.

Write to me, and you’ll unlock rooms, stories, and fresco details most visitors never notice. Don’t leave Bologna without hearing them.